The Tradition of Traditions – The Japanese Tea Ceremony

Although the bustling metropolis of Tokyo progresses toward a more modern pace, there are many traditions in Japanese culture that keep the population grounded, and its identity well-established. As one of the most long-lasting traditions, the tea ceremony, called chadō(茶道), is still practiced to this day, and has endured for hundreds of years since the introduction of green tea from China in the 9th century.

A display of elegance and high-class hospitality, while also serving as a reminder to enjoy the simplicities of life, the tea ceremony, also called ‘The Way of Tea,’ should be experienced at least once in your life. Understanding the core fundamentals of the ritual, as well as the importance of each element of the process to the overall experience, will allow you to get more out of it.

Table of contents

History of the Japanese Tea Ceremony: Then and Now

Since around the year 815, when Buddhist monk Eichu made tea for Emperor Saga after bringing back seeds from Tang Dynasty China, a never-ending love affair with green tea was born in Japan. In its early stages, Japanese green tea was a luxury reserved for the upper class, including political and social elites.

As it later spread and became much more widely available, tea was consumed to sustain good health, and the serving of tea at the start of the New Year became ritual to repel illness, particularly during the Heian Period when disease ran rampant.

Later on during the Kamakura Period, around the year 1235, the formal Japanese tea ceremony began to take shape. This started with the Eihei Rules of Purity written by Zen monk Dogen, wherein the foundation of the modern tea ceremony is believed to be contained. It was also during this time that ceremonies for the general public were opened in places like Nara’s Saidaiji Temple.

Perhaps the biggest push forward in framing the tea ceremony as we know it today comes from Zen monk Murata Juko, who brought the Wabicha method, infusing the Zen principle of chazenichimi, which placed heavy emphasis on simplicity. This solidified the spiritual aspect of tea ceremony, as previously imparted by monks like Eichun and Dogen who had come before.

A little over a century later in the Muromachi Period, Takeno Joo, along with his student Sen no Rikyu, carried on with Murata Juko’s style of tea ceremony. In being the most influential masters of the ceremony, Joo and Rikyu had a tremendous impact on nearly every aspect of Japanese culture, from the arts, to philosophy and much more.

In the present day, there are many different styles of Japanese tea ceremony, but all are still deeply rooted in the Zen-inspired foundational principles of respect, inner and outer harmony, and simplicity established centuries ago.

The Japanese Tea House: A Serene Sanctuary

As the tea ceremony is heavily steeped in Zen philosophy, it comes as no surprise that the structures in which these rituals take place would follow the same tenets. Traditional tea houses, or chashitsu, are built with simplicity at the core of their design.

The Garden Area

Signifying the tea house’s connection with nature, in addition to its own design, the front of the house traditionally faces a roji, which is a quaint garden that easily sheds the noise and haste of the outside world. Prior to entering the tea house, you should be prompted to watch your hands as a preparation for the ceremony.

Inside the Tea House

For a traditional Japanese tea house, you will enter through a small crawl space, called the nijiriguchi. This space offers a humbling charm, in that it signifies everyone as being equal in rank, despite their status in the outside world. This is another part of the ‘purification’ process of the tea ceremony, as the inside of the structure is akin to a womb, and the act of using the small entrance is to strip yourself of your position in society, becoming pure as a newborn.

Once in the tea house, you will find yourself in the main room, where the tea will be served. The design will be minimal and earthy, as it should be, with tatami mats for flooring, and shoji sliding doors and windows made from wood and Japanese paper. The space inside can be quite compact, to convey a closeness between the server and guests.

-

Koma

– This size tea house is smaller than 8.2m², or fits less than 4½ tatami mats

-

Hiroma

– This size tea house is larger than 8.2m², and can fit 4½ or more tatami mats

There will also be a small recessed space in the room, called a tokonoma, with modest decoration for you to admire prior to the procession of the ceremony. Other than this main room, there is typically only one other room, called a mizuya, where the tools for carrying out the ceremony are washed and prepared.

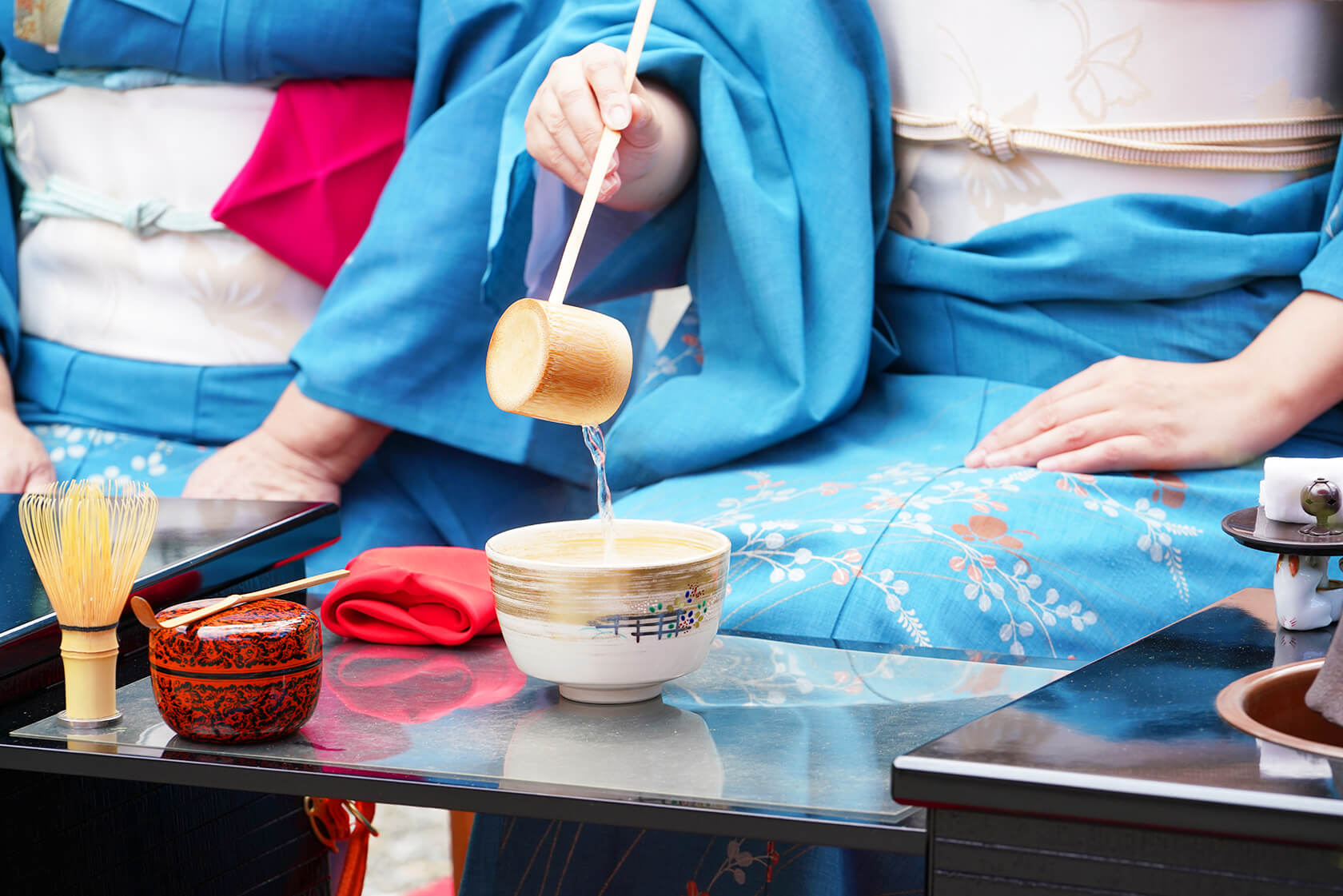

Equipment and Utensils Used for the Tea Ceremony

There are specific tools used in a traditional Japanese tea ceremony. Here is a list of items you should expect to see, with their specific function.

-

Chashaku(茶杓)

– Made from bamboo, this utensil is a crucial part of tea preparation. This scoop helps to measure the proper proportion of matcha powder.

-

Natsume(棗)

– This short, round wooden container is used to hold thin matcha powder.

-

Fukusa(袱紗)

– This is the cloth used to clean the chashaku and natsume during ceremony. The color of the fukasa may vary based on gender, age, skill level, school or type of ceremony.

-

Cha ire(茶入)

– This tall, thin container holds the thick matcha powder used for making koicha, a special green tea blend. One of the more important pieces of equipment in a tea ceremony, the cha ire is ritually cleaned using the fukusa prior to retrieving the tea powder.

-

Chawan(茶碗)

– Arguably the most important piece of the tea set, tea could not be served or consumed without this drinking bowl.

-

Chasen(茶筅)

– A special bamboo whisk used for thorough mixing of the tea powder and water.

-

Chakin(茶巾)

– This white cloth made from hemp or lenin is used to clean the chawan once the user has finished drinking.

-

Kama(釜)

– This is the kettle or iron pot used for heating up water for tea.

-

Hishaku(柄杓)

– This bamboo ladle is used to take hot water from the kama, and place it into the chawan.

Preparing for the Tea Ceremony

The responsibilities for the preparation of a tea ceremony are equally shared by both the host and guests.

For the host, it begins with tidying the garden. As the first sight that guests will encounter when they arrive at the tea house, the garden must be at its most presentable. After that, the host will select the tools that will be used for that particular ceremony, then clean the tearoom and make any minor repairs to the tatami mats or shoji doors as necessary. If there is to be a meal during the ceremony, the host will begin preparing the meal either the night before, or early in the morning of the ceremony.

For guests, preparation is more psychological in nature. Start with clearing your mind from thoughts and concerns of everyday life outside the tea house. Additionally, as mentioned before, guests must wash their hands to complete the purification process prior to entering.

The Tea Ceremony Process

The tea ceremony follows a certain process made to illuminate the mind with precise movements and graceful hospitality.

- 1. After guests have purified themselves, they will be greeted into the tea room and seated. Some tea houses offer sweets, which will be presented at this point in the process.

- 2. Next, the host will present the tools that will be used in the making of the tea, and clean these instruments with great detail.

- 3. Now, the actual tea preparation will begin. The host will start by making a thick, almost paste-like matcha mix, first by adding the powder and then adding water. The contents will be whisked together, then more water added gently to thin out the mixture.

- 4. The mix is offered to the main guest, who will examine the bowl and sample the tea. Afterward, the first guest will clean the bowl with the cloth and pass it to the second guest. The same process will follow until all guests have sampled the tea, after which point the bowl will be returned to the host.

- 5. The host will clean the bowl a final time, along with all other instruments used for making the tea.

- 6. Guests will carefully inspect the cleaned utensils as a sign of respect for the host’s meticulousness.

- 7. The ceremony will conclude with a final bow from both the host and the guests.

A Once-in-a-Lifetime Experience

If you plan to take in a traditional Japanese tea ceremony, awareness of the underlying principles that govern the ritual can make it a more enlightening experience that will remain with you for many years.

Motto Japan, the community platform to support foreigners with the foundation for life in Japan, including Japanese study, job opportunities, and housing service. Motto Japan Media will provide a wide variety of information for Japanese fans all over the world, to create a cross-cultural environment and enrich the life of foreign residents in Japan!

Leave a Reply